Rita Willcoxon, BSIE ‘82

Rita Willcoxon, BSIE ‘82

On July 21, 2011, Atlantis landed at the Kennedy Space Center and NASA employees gathered to watch this historic event. Atlantis was the last STS–Space Transportation System, commonly known as the space shuttle–to fly on a mission. It was the end of an era, and for many employees, the end of their jobs. The mood was not somber, however; it was celebratory.

“Nobody expected us to be able to perform the way we did on these last few missions,” said Robert Cabana, the director of the Kennedy Space Center, as he addressed the crowd of employees. “You performed flawlessly right up to the very end. I can’t say enough good things about the dedication this team has.”

Cabana then called Rita Willcoxon up to the front of the crowd. As the Director of Launch Vehicle Processing at NASA, Willcoxon led the shuttle program in its final six years, and was largely responsible for the positive nature of the event. Referring to her and Patty Stratton, a contractor who worked with the shuttle program representing the United Space Alliance, Cabana said “I don’t know of any two people that care more about this team than the two standing here now. They take care of you like you wouldn’t believe.” He then awarded Willcoxon and Stratton a Distinguished Service Medal and a Distinguished Public Service Medal, for “continuous outstanding leadership contributions provided to the nation’s space shuttle program.”

In a move that was emblematic of her leadership style, Willcoxon leaned over to the microphone and gave all the credit to her employees. “It’s all about you guys,” she told the crowd. “It’s not about us. You’re the best team ever.”

A Well-Rounded Education

A Well-Rounded Education

Rita Willcoxon grew up as Rita Patterson, and went to Southside High School in Fort Smith, Arkansas. As a child, she loved math, and decided she wanted to focus her career around it. She learned about industrial engineering from IE professor John Imhoff at an orientation at the U of A. “He was so dynamic,” she remembered. “I thought, I want to do what that guy does.”

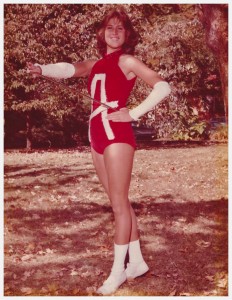

As a student, Willcoxon took on two different and challenging roles: engineering student and majorette. She has fond memories of studying with fellow engineering students and of twirling a baton on the field while the Razorback band played the fight song. In 1980 she was crowned St. Patricia in the annual Engineer’s Week celebration.

Willcoxon married her high school sweetheart Jim the summer after graduating college. Jim was attending Oklahoma City University. After she graduated, they moved to Oklahoma City, where Jim had a job as a high school teacher. Willcoxon’s first engineering job was at Tinker Air Force Base, where she focused on aircraft maintenance performing fixture design, facility layout, equipment management and logistics studies.

After a few years in Oklahoma, the Willcoxons decided to move to a warmer climate, so they both started looking for jobs in Florida. Rita found a job with the Defense Contract Management Administration. In this role, she represented the government at the Harris Corporation. From there, she started working for NASA where she had a series of jobs in the space industry, working her way up the ladder and honing her management style.

A Career in Space

A Career in Space

Willcoxon began working at Kennedy Space Center in 1988, in the Payload Operations Directorate. From there, she worked in several key leadership positions at Kennedy, led Agency-wide teams, and she had a year-long assignment at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. She has been involved in several Spacelab missions, the Magellan mission, the European Retrievable Carrier (EURECA), the Gamma Ray Observatory, and the Cassini mission. Her work supported the Space Shuttle, International Space Station and Expendable Launch Services Programs, as well as future NASA programs. One of the highlights of her career was being part of a team that designed a mission to Mars. For this mission, which unfortunately never took place, a spacecraft would convey a rover to the surface of Mars. The rover would collect samples, which it would send into orbit on a rocket. A spacecraft would pick up a payload canister full of Martian rock and soil samples, and it would convey the samples back to Earth. Willcoxon was responsible for the design and mission requirements of the rocket element of the mission.

Over the years, Willcoxon has earned numerous awards. In addition to the Distinguished Service Medal and a Distinguished Public Service Medal, she has received the Silver Snoopy award, two Exceptional Achievement Medals, the Outstanding Leadership Medal and an Exceptional Service Medal. When the Space Shuttle Program reached its final flight, the U.S. Senate honored the men and women of the program with Senate Resolution 233, and Willcoxon received a personal copy from Senator Bill Nelson with a thank you note.

In the course of her career, Willcoxon’s industrial engineering point of view proved useful. She is an expert in the ways technology and people work together, and she worked to ensure that NASA’s systems were designed to be operated and repaired easily and cost-effectively. While mechanical and electrical engineers focus on how devices and systems work and how much they cost to build, it is the role of an industrial engineer to look at how these designs affect the people who interact with the technology.

“When you are operating a vehicle, it needs repairs and maintenance,” Willcoxon said, explaining that this raises several questions for an industrial engineer. “How many times will you change the parts? What materials will you need? Will the parts need to be uniquely made or will they be standard? How much staff will be required to maintain the vehicle? What is the schedule timeline?”

In addition to her careful application of industrial engineering principles, Willcoxon strongly believes that relationships among people are vital to the success of any endeavor.

“In everything you do, the people are key,” she explained. “That’s why my number one priority is the people. Because I feel like if I take care of them, they take care of everything else, and so I really emphasize that more than anything.”

The Space Transportation System

The Space Transportation System

In 2006, Willcoxon became the Director of Launch Vehicle Processing. In this role, she was responsible for the launches of the Discovery, Atlantis and Endeavour shuttles, and she managed approximately 5,400 civil service and contractor employees.

The first space shuttle, Columbia, launched in 1981. Over the next three decades, these vehicles carried more than 600 crewmembers and over 3 million pounds of cargo into space. During the six years that Willcoxon oversaw the program, Discovery, Atlantis and Endeavour launched 21 times, carrying astronauts, supplies, laboratories and equipment for the International Space Station. In previous years of the Shuttle Program, the shuttle carried communications and defense satellites, and they transported interplanetary spacecraft, such as Gallileo, and telescopes, including the famous Hubble Space Telescope.

Willcoxon was the first and only woman to have this NASA Director position. She explained this as a sign of changing times. “This organization for a long time was mostly men,” she said. “If you look at my direct reports right now, 50 percent are women.”

When it came to her gender, Willcoxon said, “I’ve really not felt like there’s been any holdback at all. Maybe it’s just my personality. I’m never going to back off of an opportunity. If somebody thinks I can do something, I’m going to step up and try to do it.”

Integrating Technology and People

Integrating Technology and People

Willcoxon and her employees were responsible for making sure that the space shuttles were completely prepared for their journeys. The contents of the shuttles, called the payload, had to be carefully designed, prepared and packed away for the journey, and Willcoxon’s industrial engineering training and previous payload experience made her an expert in the processes needed to make sure each shuttle’s payload was safe and secure.

Before a shuttle launched, workers had to check that all the components of the payload had been tested to make sure the materials would survive in the harsh environment of space, and that all the equipment would work properly. Then, they had to figure out the best way to integrate the payload into the shuttle. It needed to be securely held in place, making the best use of the limited capacity of space and weight the shuttle had to offer. Finally, the entire arrangement had to be thoroughly tested through simulations and everything had to be double checked before launch.

The shuttle missions involved complex arrangements of equipment and technology, but Willcoxon pointed out that behind each mission there was also a complex arrangement of people. Willcoxon and her teams worked alongside government contractors, university faculty and employees of other NASA labs, such as the Jet Propulsion Lab. Each group had a distinct culture and a different set of norms and expectations. Like the different components of the payloads, these had to integrated so they could work together effectively.

“At Kennedy, everything came together,” said Willcoxon, explaining that she used similar problem solving skills on both technical and human problems. “You’ve got to be very customer-oriented when a lot of people and organizations are giving you requirements,” she explained. “A lot of people are throwing things your way, so you’ve really got to be able to have a lot of patience, and you’ve got to be able to work really well with other people. You’ve got to work hard to understand what it is they need you to do with their hardware that they’re bringing here, and that now you’re responsible for integrating it all together and getting it ready for launch. So there’s a lot of communication, a lot of forums.”

For Willcoxon, solving human problems meant being accessible to everyone she worked with, and paying close attention in order to catch issues before they became a problem. “I have small group meetings with people to talk one-on-one about what their issues are,” she said in her oral history. “It’s just another way to make sure that they know that I’m always there for them, and that my focus is on the people.”

Once the space shuttle program ended, Discovery, Atlantis and Endeavour were moved to their final homes in museums, where they will be remembered and honored. Willcoxon explained that the thing she is most proud of in her career is the way she was able to honor the employees who had worked in the program, as well. Her employees made a “human shuttle” in a parking lot and videotaped it for YouTube. Willcoxon honored all the shuttle employees who had been with the program from the beginning as “Shuttle Legends”, conducting special ceremonies and providing them with a Shuttle Legend patch. She and her management team even organized a Jimmy Buffett concert for employees after the last shuttle launch. “I tried to make people feel special, pointing out to them that they were a part of history” she said. “They had a tremendous amount to be proud of.”

Five months after the shuttle program ended, Willcoxon began a job at General Electric, Transportation. Willcoxon was still looking out for her employees, and brought several of them with her from NASA to GE. In a more down to earth role, she led a group that put intelligent controls inside locomotives and along train tracks. These systems included safety software and electronic systems that could save fuel and optimize trips. This job took her around the world, to Europe, the UK, Australia, Brazil and all over the United States. After nine months, she decided to back off from the travel, moving down to part time, and then retiring after four years with the company. She and Jim live in Florida, where he was the Principal at Melbourne High School. They have two children, a daughter Erica, who is 26 and a son, Grant, who is 21.

With a little more time on her hands, Willcoxon has decided to spend more time at the school where she started on her career path. She visited the University of Arkansas last fall, connecting with the Department of Industrial Engineering and taking part in a Society of Women Engineers career panel, as well as reuniting with her fellow baton twirlers, and Pi Beta Phi sorority sisters. After a career filled with solving technical problems and helping people work together, Willcoxon can now use her engineering and management skills to provide a role students in the College of Engineering, and they are lucky to have an opportunity to benefit from her knowledge and experience.

“Never stop learning,” is Willcoxon’s advice to students. “Don’t get comfortable. Always push yourself. Don’t be afraid to do something different.”