People don’t usually associate engineering with art. We often think of these two disciplines as opposites, and assume that few people are interested in both. But as several of our alumni have shown us, engineers can make great artists, and artists can make great engineers.

Learning to See

Barney Baxter, BSChE 1948

When Barney Baxter took up painting, he had to learn to see things in a new way. As an art instructor said to him, “you engineers are so locked into the truths of what you know that you have trouble painting what you see.” Learning to forget what he knew about a subject and simply see it as it is was a key lesson, Baxter explained. For example, when painting railroad tracks running into the distance, an artist has to “forget” that the two tracks run parallel and paint them as if they are moving toward each other. Artists also have to learn to really see colors, and perceive how the same object can look very different under different light intensities.

Barney Baxter’s interest in art began in 1942, when he took engineering drawing, but he wasn’t able to devote himself to art until recently. Baxter had a notable career, serving as president and CEO of CF Industries, a Fortune 500 company, and later owning a chemical company. When he retired at the age of 85, Baxter was able to find the time to “literally get lost” in his paintings, spending two to four hours translating abstract inspiration or the scene before him into images on canvas.![photo[1]](https://bpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/wordpressua.uark.edu/dist/7/112/files/2015/01/photo1-300x226.jpg)

Baxter also compares painting to a skill he’s developed over the years: business management. “Painting is not that much different from managing,” he explained. “You are bringing form and artistic order to abstraction.” As a manager, he took people, machinery and resources and put them together to create a successful business. These days, as a painter, he combines ideas with paper and paint to make his art. There is one significant difference however: painting involves much less risk. “If I’m in front of an easel with my paint and I happen to blunder, it’s easy, I just paint over it,” he explained.

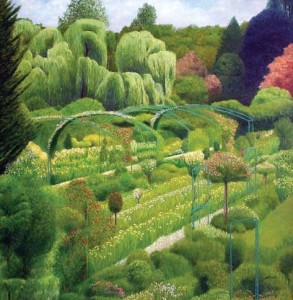

Landscapes are Baxter’s favorite things to paint. Recently, though, he’s become interested in portraits, following in the footsteps of his mother-in-law, who was a portrait painter until age 97. A couple years ago, he and some fellow artists converted an empty building in their community into an art studio and brought in an instructor to help them with advanced painting techniques. Baxter is even thinking about expanding on his art, taking up sculpture in addition to painting.

Continuous Improvement

Jim Hefley, BSIE 1961

As an industrial engineer, Jim Hefley has always believed in continuous improvement. He applied this concept to his career at IBM, then as a business consultant. When he retired from Gemini Consulting in 2000, he began taking painting classes, and discovered he really enjoyed it. Now, Hefley is busy with his third career as an artist.

Hefley paints many different subjects: local landscapes, fishing scenes and European scenes that are based on photographs he’s taken on trips. He explained that his engineering background especially helps him with the composition of his painting: arranging the focal point and analyzing the relationship of the other elements in the painting to establish proper perspective.

Though Hefley explained that he’s had to expand the creative side of his brain since becoming an artist, he pointed out that art and business have a surprising amount in common.

“A lot of people, including most artists, don’t appreciate the degree to which you can be creative in business,” he said. “Maybe I’ve sought out those assignments, or maybe they’re always there. I’ve always thought finding new things, new processes, new systems, is a creative process, just like art.”

Still a savvy businessman, Hefley began selling his art a few years ago, and he donates the profits to charity. Currently, Hefley donates 90 percent of the money he makes from his art to an organization called Trout Unlimited, which is dedicated to protecting and restoring coldwater fisheries and their watersheds. Hefley’s contributions directly support one of Trout Unlimited’s youth camps, which teach local kids about fishing and conservation.

Hefley also donates 10 percent to non-profit groups that support breast cancer patients. He contributes to the Hope Cancer Center for Women in his hometown of Asheville, North Carolina and to Casting for Recovery, an organization that enriches the lives of women who are breast cancer survivors by combining education, peer support and fly fishing retreats.

The Artistic Side is Everything

Kent Burnett, BSIE 1968

For Kent Burnett, engineering and art have always been interrelated. He was inspired by his uncle, an artist who drew renderings of space shuttles for the Lockheed company and took photos of cars in his spare time.

Burnett discovered photography when he was twelve years old. The owner of a repair shop in Burnett’s hometown of Mena, Arkansas, had a darkroom and let Burnett use it. It was there that he learned about framing and lighting a photograph, as well as the creativity involved in processing the image.

When he began studying industrial engineering at the U of A, Burnett discovered that “the artistic side was everything in engineering.” In his classes, Burnett used his artistic skills to make line drawings and diagrams, as well as using the creative and observational skills he’d honed through photography.

Burnett enjoys combining travel photography with candid shots of people, capturing the look on someone’s face as they observe a piece of art, for example. He has taken photographs in the Swiss Alps and on African safaris, and he loves returning to the same location to retake a picture with a new camera. “Travel is the reason for photography and photography is the reason for travel.”

Burnett has had a successful career with Dillard’s and in his current job, his career and his photography have come closer than ever. As vice president of technology, Burnett deals with e-commerce, which, he explained is “all about images on the Internet.” In this capacity, Burnett works with photographers, stylists and models to take and publish many images in a short amount of time, and his understanding of photography, technology and project management all come in handy.

In his spare time, Burnett continues to pursue his own photography. “It rounds out your life having a hobby like that,” he explained. Recently, he sold his first photographs at a show, and after decades of a successful career in business, it’s the money that he received for those pieces of art that means the most to him.

I’m Better at Everything I Do Because of the Arts

Michael Weir, BSCE 1998

Michael Weir didn’t begin his career as an engineer. In high school, he played the violin and was active in theatre. In college at UALR, he earned a double major, studying radio, T.V. and film as well as theatre. He worked as a news producer for television stations in Fort Smith and Tulsa, but after a while, he decided to pursue a different career.

Weir’s father, Larry Weir, is a civil engineer from the U of A, so in his second career, Weir decided to follow his father’s footsteps. After earning an engineering degree, he worked for Engineering Services Inc. in Springdale for 15 years. In this job, he mainly worked designing rural water and wastewater systems.

Weir thought his theatre days were behind him until someone from the Arts Center of the Ozarks contacted him and said “You used to be in plays, didn’t you?”

“I discovered the Arts Center and never left,” Weir said. For over a decade now, he has acted in a couple plays a year. Most recently, he played the role of Max Detweiler in “The Sound of Music.” Acting is a big commitment of time and energy. Weir explained that for each play, he spends five to seven weeks rehearsing, devoting his evenings and weekends to the theatre. Luckily, he had the support of both his employer and the Arts Center to help balance his career and his hobby. “ESI was great about supporting my acting,” he explained. “In turn, the Arts Center is great about adjusting to the busy lives of its volunteers whenever possible.”

About a year ago, Weir left ESI to start a real estate business with his wife, and his schedule is now “very busy but very flexible,” making it even easier to pursue his acting as well as other community involvement.

Weir explained that acting increased his social skills and gave him confidence, which helped him in his engineering career. “When you’re acting, you have to have an open mind about what you’re approaching,” he said. “It’s the same with the political nature of public works. You have to adapt to your surroundings and know what to say and what not to say.”

All four of these engineers came to art in different ways at different times of their lives, but they all agree on the role that art plays in their lives. As Weir puts it, “My career makes me a living, but the arts give me a reason to live.”