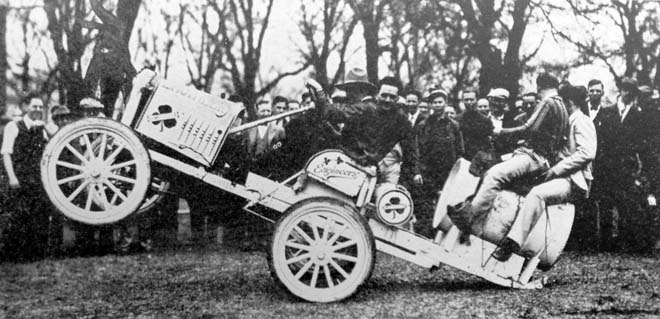

At the first Engineer’s Day in 1909, students line up on what is now Old Main lawn to see engineering demonstrations.

In the middle of a spring night in the 1940s, several engineering “knights” steal across the lawn in front of University Hall. They are carrying cans of green paint, specially formulated in a chemical engineering lab. They are heading for the Agriculture Building. The building looks dark and empty, but the engineers are cautious. When they are about 30 feet away, they pause to remove the lids from the cans and dip their brushes. Green paint dripping, they dash toward the building.

They have almost reached it when the counter attack begins. Smelly brown globs the consistency of mud shoot from a window in the upper floor, splattering on the ground and covering the engineers in foul-smelling goop. The agriculture students have engaged their manure spreader. Wiping the dung from their faces, the engineers persevere and quickly paint several large green shamrocks on the front of the building. Thanks to the ingenuity of the chemical engineering students, the paint will be impossible to wash off, and will have to be sanded from the walls.

Their mission complete, the engineering students run back across the lawn, dodging the last efforts of the manure spreader. Engineer’s Day has officially begun.

History

Beginning 1909, the University of Arkansas College of Engineering set aside a day to celebrate several things: St. Patrick’s day, the field of engineering and the glory of being a young college student with a day free from classes. The association of St. Patrick with engineering students began in 1903 at the University of Missouri in Columbia.

Like every good tradition, this one has more has than one explanation. In one version, a class discussion leads to the conclusion that “St. Patrick was an engineer, of course,” and that the following St. Patrick’s day should be set aside for revelry, to the dismay of the Missouri faculty.

The other story is more fanciful. The website of the University of Missouri explains that

According to engineering tradition, the discovery that St. Patrick was an engineer began with the excavations for the Engineering Annex Building. During the excavation, a stone was unearthed with a message in an ancient language. This message was translated into “Erin Go Bragh.” Although those of Irish descent may recognize “Erin Go Bragh” as “Ireland Forever,” the engineers loosely translated this phrase as, “St. Patrick was an engineer.” The stone, now known as the Blarney Stone, is an integral part of the St. Pat festivities. The engineers looked to the legend that St. Patrick drove the snakes out of Ireland as proof of his engineering skills. They further credit St. Patrick with the invention of calculus.

Whatever the explanation, the tradition of Engineer’s Day spread to Arkansas several years later, and eventually made its way into colleges across the nation. By the sixties, Engineer’s Day at the University of Arkansas had blossomed into an entire week of engineering and revelry.

Events

Engineer’s Day traditionally presented a balance of academic and entertaining activities. From the beginning, the holiday included lab tours and engineering demonstrations.

In 1929, The Arkansas Engineer provides a list of engineering marvels for that year. The electrical engineers exhibited “automatic motors started by voice and heat, reversing motors, rainbow wheels, Tesla coil, arc lights, high voltage and current transformers, mystic drums and lights, and a bowling alley,” while the mechanical engineers had a small replica of a steam turbine and “mysterious balloons, gyroscopes and frozen suckers.” The civil engineering department displayed “miniature roads, hydroelectric plants and a magic fountain. Also testing of road material, of cement briquettes, of steel, wood, concrete and copper columns and the measurement of the flow of water by Peitot tubes and Venturi meters.”

The most popular exhibition of the twenties was something called the Bucking Ford, which, according to the magazine, “did just what the name signifies.”

The engineers showed off their skills in other aspects of the celebration, as well. In addition to the non-washable paint, Colonel William Myers, an alumnus and former faculty member in the chemical engineering department, remembers another yearly triumph of the engineers.

Where the science building is now in those days was the engineering shop and power plants. All engineers had courses in foundry work and blacksmithing. There was a big steel silver chimney. A few days before Engineers Day, every year, by some mysterious means there would be a large green shamrock five feet wide painted across the top. The chimney was at least a hundred feet tall. A few days after, the physical plant would paint it over, and it was a major operation. They would have a crane and chains and ropes and five people and it would take them all day. But it always appeared as if by magic.

While the painting of shamrocks was always an unofficial part of the celebration, frowned upon by faculty and administration, the day included plenty of less dangerous events. During the forties, the engineering students put on a fireworks display for the whole town, which Myers called “the best in Northwest Arkansas.”

Throughout the years, the celebration also featured banquets, a tug of war against the College of Agriculture, basketball games, a beard-growing contest, a dance, and the presentation of the Chicken Award. According to The Arkansas Engineer, the Chicken Award ceremony “is where a few brave students present ‘awards’ to professor in various departments who have gained a certain measure of ‘renown’ for deeds above and beyond the call of duty.”

Robert Babcock, professor of chemical engineering, has observed the Chicken Award presentation, and admits that he always suspected the recognition was a little tongue-in-cheek.

The cornerstone of the celebration was a rally where male engineering students and female students from across campus competed for the honor of being named St. Patrick and St. Patricia.

According to the student magazine, “the only requirements for St. Pat was that he had to be at least a junior enrolled in the college of Engineering. The requirements for St. Patricia were ‘any female member of the student body of the University of Arkansas, of comely facial feature, pleasing personality, and streamlined curvilinear contour.’”The College of Engineering, which was entirely male until the forties, and mostly male for long after that, took the choosing of St. Patricia very seriously. “Our Queen,” proclaims the student magazine, “chosen by popular acclaim, symbolizes the Engineers’ one manifestation of taste for beauty. Since the days of St. Pat, the hard boiled sliders have demonstrated the most abject servility to their Queen. They have always gladly suspended or even abandoned their everlasting pursuit of the elusive X to do her will.”

The engineers’ one manifestation of taste for beauty appeared in the form of photo spreads in the magazine during the 50s and 60s, but the real contest came during the yearly rally, where St. Patrick and Patricia candidates sang, danced, and participated in skits. The winning couple was crowned at the end of the event, and their main duty was to declare the senior engineering students to be Knights of St. Patrick.

Feud and Controversy

Not surprisingly, this event, organized yearly by undergraduate students, was often the subject of scrutiny. In 1934, George Stocker, dean of the College of Engineering at the time, wrote an editorial in the Arkansas Engineer, suggesting that Engineer’s Day would be more valuable as a recruiting event than a college celebration, and he complained that all the planning was left to the last minute and that the purpose of Engineer’s Day was unclear.

Later issues of the magazine lament the lack of participation in Engineer’s Day, and sometimes bemoan the undignified content of the skits at the rally, but the most controversial aspect of the event was the feud between engineering and agriculture students.

Feuds between colleges were not limited to the University of Arkansas. An article in the student magazine for the agriculture college suggests that the idea of using a manure spreader in pranks against other colleges came from another university. Babcock remembers that engineering students at his alma mater had a feud with the Law School.

The engineering/agriculture feud at the U of A threatened to end both Engineer’s Day and Agri Day when the pranks got out of hand. The agriculture students, who traditionally painted white footprints around campus before Agri day, were attacked by a high-powered hose one year when they attempted to paint the sidewalk in front of Engineering Hall. In 1947, engineers painted an entire picnic lunch that was left unattended on the back porch of an agriculture fraternity house, and the following year, the agriculture students whitewashed two sides of the engineering fraternity house.

This was the last straw for the administration, and in 1948, Dean Stocker formed a committee composed of the deans and student leaders from the two colleges.

The committee resolved to limit pranks to painting on sidewalks with washable paint, and the celebrations were allowed to continue.

Engine Week Today

Engineer’s Day, now usually referred to as Engine Week, continues to this day in the College of Engineering, but after the feminist movement of the seventies, the fading importance of St. Patrick and the eventual death of the engineering/agriculture feud, it is a very different event. The St. Patricia photo spreads ended with the sixties, and in 1979, Anne Lynch, the editor of the student magazine, pointed out that St. Ferdinand III, not St. Patrick, is the official patron saint of engineering. Shamrock painting, washable or not, is now a thing of the past.

The current version of the celebration features wholesome fun and educational activities, and often Engine Week coincides with National Engineers Week. In 2011, the event featured speakers on nuclear safety systems and spacewalking, several sports contests, tailgating, an engineering trivia contest, a picnic and the “Flying Egg Crash Lander,” a contest in which students dropped insulated eggs from the ramp inside Bell Engineering, hoping they will land unharmed.

During Engine Week today, St. Patrick is a distant memory, vandalism is unheard of, and women and men compete as equals. One thing remains the same, however: our engineering students are proud of their community and their accomplishments, and they know these things are worth celebrating.