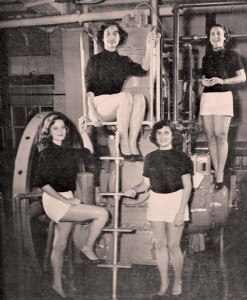

Candidates for the Engineer’s Day beauty contest, posing in the lab. Until the second half of the twentieth century, this was the closest most women got to engineering equipment.

By April Robertson

In the course of its history, the University of Arkansas College of Engineering has helped a number of women forge successful careers in engineering and leadership. The initial female graduates were few and far between, and, like every engineering college, the ratio of male to female students has never been equal, but the college’s diversity and atmosphere has come a long way since the first woman entered the college.

Dana Jesswein Steele, Betty Yanis, Marilyn Head and Lee Johns Lane, are just a few of the pioneers.

Starting it All

Dana Jesswein Steele was the first female to graduate from the College of Engineering. She earned her degree in chemical engineering in 1948 and now lives in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

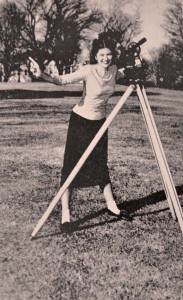

In 1948, it was very clear that the college was still adjusting to the idea of women becoming engineers. A vintage issue of Arkansas Engineer from around that time features a photo of a female student and proclaims, “Look, we even have girls in the Engine School, too!” Although female students were in the college, ads referred to them as “laboratory experts,” rather than engineers. Even the humor section of the student magazine had a gender gap, printing jokes such as, “A chemistry professor asked his class what the most outstanding contribution chemistry has made to the world,” answered with a student shouting, “Blondes.”

Female engineers were rare across the nation. Roughly 110 engineering degrees of the 35,332 awarded nationally in 1957 went to women, according to a Society of Women Engineers Panel.

Pursuing Her Passion

Betty Yanis worked to put herself through school because her father was staunchly opposed to women attending college. In 1958, she was the only female graduate from the College of Engineering, but two other ladies would graduate in the next few years. Yanis went on to University of Texas in Austin, Texas A&M in Arlington and Corpus Christi University, where she earned master’s degrees in civil engineering and economics, as well as a Ph.D. in economics. She said everywhere she went she found the same attitudes toward women in engineering: not welcome.

By the time she had earned her degrees, Yanis was simply used to it. From high school science and math classes to working as a draftsman in the engineering side of AT&T and even working for the City Engineer, she had been the only woman in all her work settings.

“It was not a big problem,” in work settings, she said, but some of her professors discouraged her pursuits. “They let me know both privately and in class that they did not want me there or even in the field of engineering.”

The ones who didn’t do this were simply “tolerant” of her presence.

Her motivation to become an engineer stemmed from a love for learning how things, especially structures worked. During a brief stint as an architecture instructor on the Fayetteville campus, she recalls being stunned by students’ lack of preparation in math and physics and felt the familiar pull, of missing engineering.

It was the natural choice for her, the girl who was always curious. “I wanted something that let me learn more than an office routine,” she said. But getting started with a career was difficult.

“Career choices for women were not given much regard,” Yanis said. “I was told by every administrativelevel that I could not even teach in the same college as my husband,” an engineer who had returned from industry into academia.

Fortunately, she landed a position with a consultant who had hired a female architect and the job proved both successful for her career and gave her a life-long friend. Betty forged a path for her career by learning to say no. “I never learned to type,” she said, and never volunteered to learn. Some of her bosses would bring all office visitors to her desk just to show off their “lady engineer,” and she was often given the most tedious tasks available.

After calculating “a zillion tons of earth from highway cross-sections,” she found a way into economics courses, earned her Ph.D. and had no trouble getting tenure track teaching and research appointments at universities. One notable moment of her career was becoming the founding Director of the Center for Business and Economics Research at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. Yanis said that she worked harder in her civil engineering undergraduate days than for any of her graduate degrees. She believes that an engineering undergraduate degree is never wasted and that it is a terrific foundation for any degree field.

Top of Her Class

Marilyn McEver Head was the only woman in the class of 1959 and she graduated as the top-ranking student that year. Only six out of 1000 American engineering students were female at the time. Head went to a polytechnic college for the first two years of her college experience and was spurred by the achievements and education of her family.

“My older male cousins were chemical majors,” she said. “We were competitive, and I thought to myself, ‘If you can do it, I can do it.”

Head’s father was the department head of chemistry at Arkansas Tech University. She had always loved to design things, so when it came time for her to choose a major, the influences of her family and her strengths came together neatly in chemical engineering. Despite being in such a minority, Head said her experiences in class and college were very favorable.

“There were amusing times,” she said, “but I was not discouraged at any point.”

Among the funnier memories were professors’ and students’ surprise that she was a girl. “My first name, Bonnie, (was known as) a unisex name, so they assumed I was a guy,” Head said. “It led to some amusing situations, but with my sense of humor, it was no problem.”

Even though there weren’t any overwhelming moments of discouragement, Head said some people believed that she would take engineering classes only to return to a life like so many women her age were leading.

“When I attended the university, most of the heads of engineering departments were retired army colonels,” she said, laughing as she recalled that one of them “wanted to give me a really good technical vocabulary so I could be a top-notch secretary.”

After graduation, Head worked for Humble Oil and Refining Company in Texas for five years. There, she said her professional development progressed normally and she didn’t encounter any discrimination whatsoever. “I received promotions and enumeration,” she said, but that was not without cost. Personal life was occasionally pushed lower on the priority list, such as the time that she missed her sister-in-law’s wedding because of transitioning a new technology into the company’s workplace. Thankfully, she said, “my husband understood because he’s an engineer, too.”

Head and her husband moved to San Francisco Bay area, and later New York, for his job opportunities. She didn’t work as a professional engineer after leaving the refinery, but her life has been just as busy as if she had. She raised three children with her husband and spent a good part of her working life standing up for disabled rights and accessibility issues, inspired by her daughter, Stephanie, who has cerebral palsy.

“My time at the U of A taught me to use skills to think clearly, to take my time and to never give up, never forget the human factor,” she said. “I hope students now learn the same things I did.”

Gaining Momentum

By 1961, six girls were enrolled in the U of A College of Engineering and another six women were alumni. The current dean of the college at the time, Dean Bratigan, wrote an editorial based on a Society of Women Engineers panel, which posed the question, “Can women engineers be effective (productive engineers)?” His opinion placed confidence in women’s abilities as engineers.

Lee Johns Lane was the first woman to graduatefrom the University of Arkansas with a Ph.D. in engineering. It was the beginning of a successful career in the aerospace industry for her. Over the years, she worked for Dow Chemical Company, Northrop Electronics, General Dynamics corporate and General Dynamics Electronics, Autek Systems and as an instructor for San Diego State and National Universities.

Now retired, Lane continues to split her time between her eight children, three grandchildren and a significant amount of boards and committees for various industry and educational efforts.

Modern Female Engineers

Abigail Washispack accepts the College of Engineering Outstanding Senior Award from Dean Ashok Saxena

While women are still a minority in the college as a whole, they are always well-represented in the pool of high-achieving students. Recently, biological engineering graduate Abigail Washispack has exemplified what women can achieve in the college.

Washispack earned her biological/biosystems engineering degree from the college in 2012 while working with professor David Zaharoff to rally student support for the burgeoning biomedical engineering program. In November of 2011, she shared her research findings on nanomaterials for biomedical applications at the Biomedical Engineering Society Annual Meeting in Connecticut. Washispack now attends the Medical University of South Carolina.

These days, female students get plenty of support from several student organizations, which can help them prepare for the competitive and challenging industry.

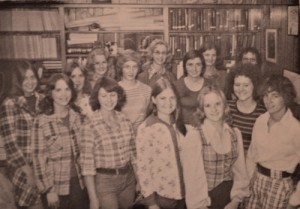

The Society of Women Engineers, Women in Engineering, Phi Sigma Rho and Engineers Without Borders are popular choices for these ladies. The Society of Women Engineers was founded in 1950 and came to the U of A campus in 1975. The local chapter has a mission to “encourage female engineers to define themselves without intimidation, through networking and with a key focus on highlighting female contribution to the engineering field with a diverse touch.” Students in this organization find a strong, welcoming sense of community with people who have a similar vantage point. They spend weekends together, working through class assignments and coordinating fundraisers that lead to national conferences, a major step in their professional development.

SWE is closely linked to Women in Engineering, which has similar activities for young professional women. The two organizations meet together a couple of times a year, when WIE members make time to speak on a panel about their experiences in the industry and prepare students for what is coming next. Many job, internship and coop opportunities develop this way and foster strong mentoring relationships.

Phi Sigma Rho is a social organization for women in technical majors. Members enjoy dinners and weekend trips as a group. They help each other with homework and weather the job search process together. The U of A chapter is one of the very few in the South.

The building of a more gender-balanced community in the College of Engineering begins before girls reach college age, and continues until graduation, thanks to recruitment and retention programs such as the Engineering Career Awareness Program, which offers scholarships to female students, and Engineering Girl Camp, a summer program geared toward female elementary students interested in math and science.

These recruitment efforts seem to be paying off: in the past five years, the number of female undergraduate students in the College of Engineering has more than doubled, from 247 to 519.