Neil Ingels, BSEE‘59, Neil Ingels spent most of his career at Stanford University and the Palo Alto Medical Foundation Research Institute in Palo Alto, California. With a Ph.D. in Electrical Engineering, Ingels had many different job opportunities, but he chose to be a medical researcher because he wanted to do something that provided a benefit to people. “I think engineers have to give serious thought to what problems they want to work on. I want to see them thinking about the application of technology to medical, economic, social and environmental problems. For example, a recent U of A team asked: ‘How can I use my sophisticated engineering ability to help people who may not have a centrifuge for medical tests?’ That’s a terrific application of engineering. I would like see more of that.” Ingels’ research has made an impact on the medical field. He headed a team that invented a technique to monitor heart motion, which has led to breakthrough discoveries about how the heart pumps blood and has influenced the treatment of heart disease, postoperative heart care and mitral valve repair. Ingels retired in 2013 from the Research Institute, but continues as a consulting professor in the Stanford University School of Medicine and an adjunct professor in the U of A College of Engineering. He is currently working on a book about the mitral valve. Using computer modeling techniques, he is taking a very close look at the geometry of the beating heart. “The deeper I get into it, the more amazed I am at this machine, this mitral valve,” he said. “I am working harder than ever, because I have so many new ideas now.”

Dylan Carpenter, M.D. BSBE ’02, MSBAE ‘04 At the time Dylan Carpenter was a student, biological engineering students could follow a pre-med path, taking engineering courses plus courses to prepare for medical school. As a graduate student, he worked with professors Jin-Woo Kim and Russell Deaton on a project to use DNA to create self-assembling nanoparticles. Carpenter knew that an engineering degree would guarantee him a good career, whether or not he ended up as a doctor. “The problem solving skills that engineering students learn, along with an understanding of the physical properties of both natural objects and machines make an excellent background for a doctor,” Carpenter explained. His engineering education gives him a useful perspective on everything from how skeletons support weight to which type of screw he should use in a surgical procedure. Carpenter graduated from the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences recently and has joined a orthopedic surgery practice in Batesville, Ark. His favorite memories from college are of the projects he completed for his classes. “That’s where you learn how to problemsolve, brainstorm, identify potential solutions,” he said. “You find the optimum solution, design it, test it, put it to use. That whole process is synonymous with the process of medical care.”

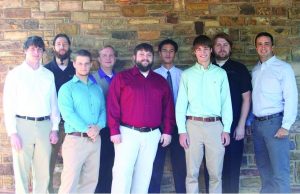

Kyle Rogers poses with U of A graduates and current students who are working at SOAPware. Left to right: Phillip Cannon, Paul Martin, Sawyer Anderson, Adam Higgins, Matthew Burton, Ross Thian, Mason Hollis, Nathaniel Johnson and Kyle Rogers.

Kyle Rogers, BS’97, Kyle Rogers is the chief technical officer for SOAPware, a company that makes software for electronic health records. Rogers, who is a member of the CSCE Advisory Board, sees the relationship between the university and the local community from several different perspectives. As an alumnus and supporter of the university, Rogers is excited to see what he calls “true software companies” emerging in the region, because they can provide jobs for U of A graduates and contribute to the evolving culture of entrepreneurship and innovation in northwest Arkansas. “I want every U of A computer science and computer engineering graduate to have a job in the area,” he said. In his role as CTO, Rogers is very happy to be near the university, which he calls “more than a resource.” Six of the 14 software developers working for SOAPware are U of A graduates, and Rogers reports that he is more than happy with their skills. One of SOAPware’s developers, Paul Martin, is currently working on his master’s degree. He started applying for jobs before he graduated, planning to start working when he was finished with his degree. He received several job offers and agreed to start working at SOAPware immediately because he was so impressed with the company. “Northwest Arkansas is a great environment for computer engineering,” he said.

Ellen Brune, BSChE ‘09, PhD ‘13 Ellen Brune became interested in chemical engineering when she visited her father at his job at the Anheuser-Busch brewery. There, she learned that the yeast used to make beer can also produce bad-tasting flavors, and she wondered why no one had created yeast that doesn’t produce those unwanted by-products. As a chemical engineering student at the U of A, Ellen applied this idea to the E. coli bacteria used to produce protein based drugs, such as insulin. On average, the products of these bacteria are 30 percent medicine and 70 percent unusable garbage. The drug industry must invest time and money to purify their products before they can be used. This amounts to an annual industry cost of approximately $8 billion. Along with her faculty mentor, chemical engineering professor Robert Beitle, Brune has produced a cell line of genetically modified bacteria that produces more medicine and less garbage. She estimates her Lotus E. coli produce 60 percent medicine, which will make it easier and less expensive for drug companies to produce pharmaceuticals. Her company, Boston Mountain Biotech, LLC, has won several prestigious business plan competitions and is participating in the National Science Foundation’s I-Corps program.