“Membranes are typically low-cost. They are modular, which means you can scale up very easily, and typically they are environmentally benign.”

Ranil Wickramasinghe, Professor and Ross E. Martin Endowed Chair in Emerging Technologies

“Garver’s Water Design Center is a knowledge center,” explained Steve Jones, a Garver vice president and director of water services. “It brings together engineering disciplines for complex water and wastewater designs.”Garver is a multi-disciplined engineering planning and environmental services firm, and its Water Design Center combines the expertise of process, electrical, mechanical, computer and chemical engineers. The center employs around 20 engineers and technicians, and the majority, including Jones, have graduated from the U of A. In fact, Jones explained that the university, with its supply of talented engineering graduates in all the disciplines Garver needs, was the main reason the company chose to open a Fayetteville office.

“What I notice about U of A grads is that they have a sense of commitment to the community, a sense of duty and a sense of pride,” added John Cutright, the center’s process group leader. “They have a desire to give back.” The Water Design Center team explained that these characteristics are important, because the center is team oriented, a place for employees who want to be part of something bigger.

The Water Design Center focuses on projects in Arkansas and the surrounding states, but they have several national projects. Recently, the company was recognized with a Grand Conceptor award from the American Council of Engineering Companies of Alabama for their design of the Tuscumbia Water Treatment Plant, the first dual series membrane plant in the state of Alabama.

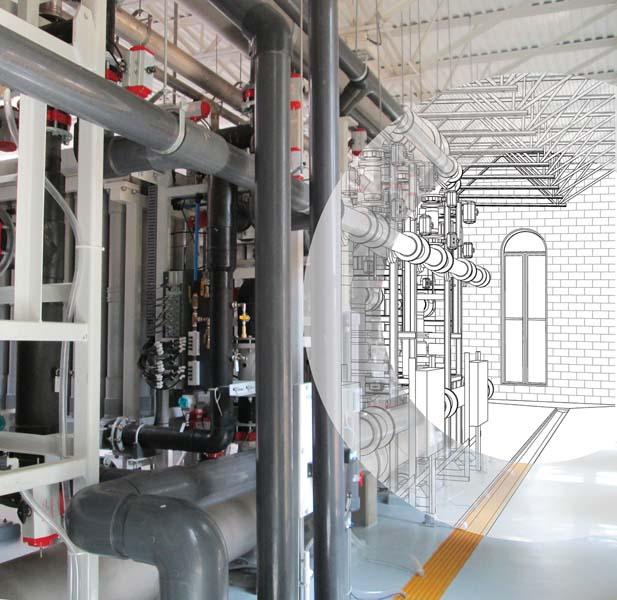

This image combines Garver’s innovative design for the Tuscumbria Water Treatment Plant with a photo of the actual plant.

The Tuscumbia plant uses membranes, filters with tiny pores, to remove pollutants and minerals from drinking water. Garver’s design for the plant involves two types of membranes: an ultrafiltration system, in which water passes through a membrane at low pressure, and a nanofiltration system, in which water is forced through a membrane at high pressure to remove dissolved species such as multivalent ions. The design center team explained that this dual process removes many of the precursors of disinfection byproducts, as well as taking out pollutants and pathogens.

The use of membranes to filter water is a relatively new approach, and Garver is working with chemical engineering researcher Ranil Wickramasinghe to improve this technology. He is developing responsive membranes that are less likely to get clogged, or fouled.

“Membranes are typically low-cost. They are modular, which means you can scale up very easily, and typically they are environmentally benign,” explained Wickramasinghe. “The downside with membranes is that it’s very easy for contaminant species, for the things you’re trying to get rid of, to deposit on the surface of the membrane, and it clogs the membrane, which leads to reduced performance.”

Wickramasinghe is using a couple of approaches to prevent membrane fouling. One of these is to induce mixing on the surface of the membrane, keeping the particles moving around so that they don’t settle and block the membrane’s pores. Another approach is to modify the surface of the membrane with chemicals, which can repel the foulants.

Garver and Wickramasinghe hope that better performing, more efficient membranes could lead to better water treatment and even water reuse—converting waste water into drinking water. In places where clean water is scarce, water reuse could be a valuable conservation tool.

The close connection between Garver and the U of A benefits everyone: the company, the university, our students and the community. When academia and industry work together, they can create better jobs for our local economy and better technology for everyone.